Sounding Right vs. Being Right: Making AI a Reliable Partner in Safety Analysis

AI can analyse safety reports in seconds, but it's a master improviser. Learn how structured workflows turn promise into reliable insight.

1. Introduction

Picture yourself facing a mountain of incident reports. Heck, if you're reading this there's a good chance that no imagination is necessary! Each report tells a small story: a maintenance worker's boot catches a loose cable, a forklift operator misjudges a turn, a supervisor notices a guardrail that should have been replaced months ago. You're convinced these narratives hold the key to preventing the next serious accident, but finding patterns in hundreds of these accounts is like trying to recognise a tune in a crowded bar.

You've got your hands in your hair, your coffee's gone cold - but then it dawns on you like the first ray of sunshine on a cloudy day: AI! And not the finicky tech-wizz machine-learning something-something AI of yesteryear. No, those modern do-all large language models (LLMs) that you've already used to write many a tedious email in the last few years. Surely they can cut through that cacophony and deliver to you a clear chorus of insights at a simple request? And I'll admit, the first time I watched ChatGPT digest a month's worth of incident reports in seconds and spit out trend summaries, I was impressed. What would take a human analyst weeks appeared on my screen in moments.

But my enthusiasm hit a wall. Beneath this impressive performance lurks a subtle danger I've come to respect.

These systems don't think like analysts; they predict what you'll approve of. Like master improvisers, they weave together plausible narratives that can feel indistinguishable from expert work. Where a spreadsheet either calculates correctly or throws a visible error (or at least an answer that seems wildly wrong), an LLM can produce fluent answers that sound right even when they are wrong. I've learned that success requires more than good prompts; it demands a rigorous framework that keeps these powerful tools honest.

2. The Illusion of Understanding: What LLMs Actually Do

To understand why AI can make a dangerous safety analyst, let me walk you through how (I've come to understand) it actually functions. Large language models succeed by predicting one token after another rather than by reasoning about cause and effect. They do not "read" a safety report the way you or I would; they statistically estimate the most likely continuation of your prompt based on patterns in training text. And yes, this training text will have contained many great examples of cause and effect correlation - however, these models also go through extensive post-training, where they are moulded and tamed into complying with instructions and producing affable responses. That's the mass market appeal.

This mechanism creates three specific risks I've watched safety professionals (and others!) stumble into: false confidence, loss of nuance, and inconsistency.

The Risk of False Confidence. The primary danger is that an LLM prioritises sounding logical over being logical. When context is incomplete or messy, the model will often "smooth" the story to keep its output coherent, even if reality is incoherent. This bothers me more than any other limitation.

I'll go over a healthcare study that makes this risk tangible. I like to make a point of it because, when I read it, it really helped me put my finger on something that had been bothering me about LLM AIs for a while. On the surface, the results of the study looked promising: the model's classification of topics aligned with human themes roughly 80% of the time [1]. But the more important finding was what happened in the instances when the data it was tasked with processing didn't make sense. When human reviewers marked a topic as logically incoherent, the model still labelled 96% of those incoherent topics as coherent [1].

Take a moment to appreciate what this means. The AI was constructing a cohesive theme where the sub-themes of the text were in fact divergent - it so desperately "wants" to be helpful, even when when being helpful backfires! For a safety manager, that's the smoking gun: the model can confidently impose structure on noise by presenting half-formed patterns as if they were solid findings.

The Speed vs. Nuance Trade-off. The second issue is one I see teams discover the hard way: while AI is fast, it often struggles to read between the lines. In one experiment about analysing text messages about medication adherence, the AI completed the task in minutes (about 97% faster than human researchers), but agreement with human coding was only "fair" (about 37-47%) [2]. Upon inspection, the reason wasn't mysterious: the models interpreted messages literally and missed implied meaning, slang, or subtext [2].

At first I didn't grasp the relevance to a safety context, but the parallel is obvious to me now. A report that says someone was "a bit off today" could signal fatigue, impairment, or stress. A human reads the workplace context, they dig a little, they follow up. A single-pass LLM may file it under a bland health note and move on.

Inconsistency in the "Black Box". Finally, here's something that catches people off guard because it runs counter to what we are used to getting out of computers: LLM outputs can vary across runs because generation involves stochastic variables (read "random stuff"). I've seen this myself—rerunning the same dataset can yield different summaries, themes, or priorities, especially when prompts are broad or ambiguous. Most people don't discover this because performing a second run and doing a side-by-side is so much more tedious than just accepting the beautifully formatted response you got the first time. This variability is one reason qualitative research reviews emphasise reproducibility challenges and the need for careful methodology and validation when using LLMs [8].

3. What the Research Really Shows

So, if LLMs are prone to hallucination and literalism, are they then useless for safety? Not necessarily. After working through scholarly articles on the topic, the research trend seems consistent to me: structured use can be valuable; unstructured use is risky. Allow me to walk you through some examples in a way that I hope will make clear my conclusions at the end.

The Strength: High-Volume Sorting. When the task is tightly defined, especially classification, LLMs can perform extremely well. In construction safety, researchers fine-tuned multiple lightweight language models to classify OSHA accident narratives and found strong performance. Ensemble methods performed best, with a top F1 score around 0.93 [4]. That is a practical result, and one I do find genuinely exciting: for the "grunt work" of screening and tagging large volumes of reports, LLMs can be a reliable force multiplier, provided the categories are clear and the workflow is controlled.

"But wait...", I hear you say in confusion. Didn't I tell you just a few paragraphs ago that the models tend to miss subtle content subtext? The key here is that rigour is achieved by running the same data through a funnel of hard-coded steps that each try to combat known LLM shortcomings. More on that below.

The Weakness: Determining Causality. Here's where my optimism gets checked again. Performance drops when the model must explain why an incident happened. In a study applying the Gemma-2 model to Swiss healthcare incident reports, event extraction was strong (about 92% accuracy), but identification of contributing factors dropped to about 72%. The authors noted hallucination and interpretation issues in that deeper layer of analysis [5]. This is the boundary safety teams must respect: AI can be a scanner, but it is not a good diagnostician. I've seen too many people miss this distinction, probably because it is hard to resist: after all, if you ask it to diagnose, it'll try to do so... and make a good show of it too!

The Solution: Structured Prompting. Now, the gap between "good sorting" and "bad reasoning" can often be narrowed by changing how we ask the model to work. Instead of dumping data into a single prompt ("Summarise these incidents"), structured workflows force the model through stages. This includes drafting candidate themes, refining them, checking evidence, and only then summarising. Research on LLM-assisted qualitative analysis highlights that stepwise or staged prompting can materially improve coverage and reduce brittle, overly-polished outputs [3].

The practical directive for workplace safety is simple, and it's one I return to constantly: don't accept conclusions that appear in one jump. Make the model grind through the paces with explicit steps: identify, justify with quotes, score, aggregate, and then summarise. In the academic work, several other techniques are mentioned (model ensembles are particularly interesting) but I won't go into a detailed exposition here.

The Safety Net: Human Oversight Even with structure, the literature consistently emphasises something I believe deeply: triangulation. This involves continuous human validation to mitigate bias, preserve context, and catch subtle misreadings [6]. And for classification tasks, using multiple models (or model "ensembles") can increase stability and reduce overgeneralisation compared with relying on a single model [4]. In short: AI can highlight patterns at scale, but human expertise is the safeguard against confident invention.

4. The Danger Zones: Where AI Analysis Breaks Down

Even with improved structures, certain tasks remain high-risk. I already touched on some of these points but I want to clearly list the specific pain points now that the shape of my overall argument has been laid out.

Subtle Interpretation (The "Slang" Problem). Remember that medication text-message study? It showed that models often miss implied meaning and interpret language too literally [2]. In safety reporting, this worries me because culture signals and "between-the-lines" cues (fatigue normalisation, quiet pressure to rush, informal workarounds) can vanish if you rely on surface keywords.

Quantitative Aggregation (The "Math" Problem). Here's something that surprises people, but really shouldn't: LLMs are language engines, not counting machines. Without external tooling and explicit methods, they can distort frequencies, overweight common phrases, and underplay rare-but-catastrophic events. This is especially dangerous because fluent summaries can sound statistically grounded when they're not. I've caught this mistake more times than I can count (I guess I'm not a counting machine either). Use them to score qualitative data, then use good old fashioned calculation to do the statistics. Some of the LLM provider native interfaces now include tool availability for flagship models, e.g. allowing them to compose and execute python scripts, but this does not carry over to simple API usage (that is, plugging it into your system in a standard prompt-answer/input-output setup).

Large, Noisy Datasets. Context limits force the model to see only fragments of long logs at once. Reviews of LLM use in qualitative research highlight contextual limitations and occasional inaccuracies as persistent barriers [8]. In practice, this can mean missed "slow-burn" trends and invented glue that stitches partial context into a confident story. It's like asking someone to understand a novel by reading a random sampling of pages. They might miss the critical event that explains the antagonist's villain arc.

Bias-Sensitive Analysis. Training data reflects dominant perspectives (either in the training data or in the reinforcement training), and this matters more than most people realise. Bias analyses of LLM outputs show measurable skews that can intensify as models scale [7]. For safety teams, this matters: it can shape which risks feel "typical," whose hazards get emphasised, and which groups' issues are under-identified. Unless humans actively validate and correct.

These vulnerabilities mean that unassisted LLMs can simulate analytical rigour while delivering inconsistent, occasionally fabricated results. This creates a dangerous combination when lives depend on accurate conclusions.

5. A Practical Framework for Trustworthy AI Assistance

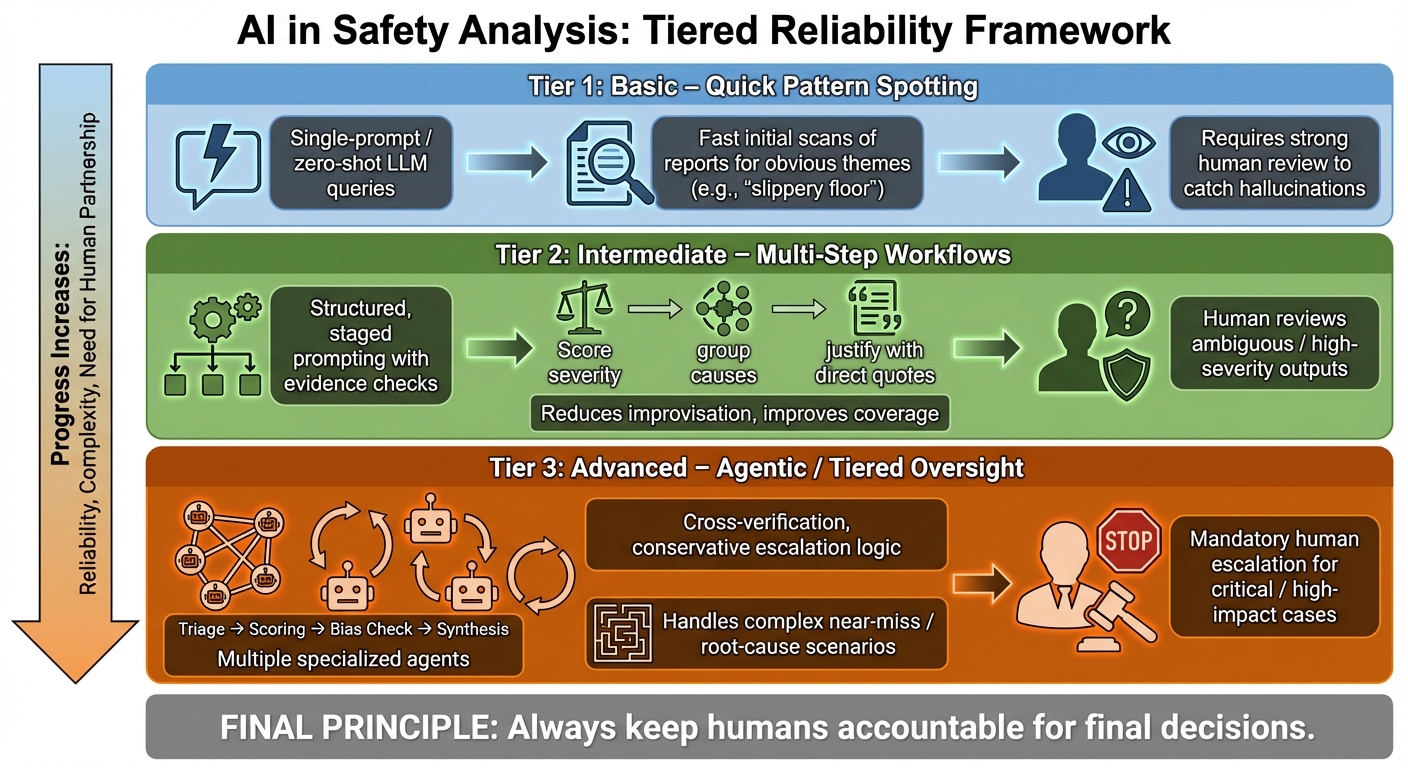

Let me reaffirm that the solution isn't abandoning these tools, but using structure that matches risk. Think in tiers: simple prompts for basic tasks, multi-step workflows for depth, and agentic systems for complex oversight [9]. This transforms AI from a liability into a disciplined assistant. Let's put it all together in a nice succinct table.

Start with hybrid workflows. Let the AI draft candidate insights, then require evidence (quotes, counts, examples) and bring humans in to validate. So-called "reasoning models" can already give you improved results on a single-prompt framework if the prompt is carefully structured and well-tested, as the "reasoning" step essentially provides a scratch pad for the model to walk through multiple workflow in a single run. For statistical rigour, compute metrics outside the LLM and ask the model to interpret the verified numbers rather than invent them. In short, a disciplined structure turns impressive mimicry into dependable analysis.

6. Building Safer Workplaces Through Smarter AI Use

Language models tempt us with shortcuts, transforming weeks of qualitative analysis into minutes. Yet their inner workings, particularly the "improviser" tendency, demand respect and structure. We've seen how they falter on nuance and causality but can excel at high-volume sorting when tightly constrained. The path forward is not blind trust or blanket rejection; it's disciplined design. We need stepwise workflows, ensemble checks where appropriate, and continuous human validation.

The folks at myosh aim to help system users squeeze real value from AI technology without offloading trust and responsibility from people onto language models (more details in a future article). This matters to me personally: safety depends on salience, judgement, and accountability: qualities that remain uniquely human. Used correctly, LLM-based tools can improve the efficiency of human attention by highlighting patterns faster, while humans remain the final authority on what those patterns mean and what actions follow.

Sources:

- Large Language Models for Thematic Summarization in Qualitative Health Care Research: Comparative Analysis of Model and Human Performance

- Comparing the Efficacy and Efficiency of Human and Generative AI: Qualitative Thematic Analyses

- Enhancing Thematic Analysis with Large Language Models: A Comparative Study of Structured Prompting Techniques

- Classifying OSHA construction accident reports: leveraging ensemble learning and lightweight large language models (l-LLMs)

- Evaluating Large Language Models for Analysing Safety Risks in Healthcare Incident Reports

- LLM-Assisted Thematic Analysis: Opportunities, Limitations, and Recommendations

- Evaluation and Bias Analysis of Large Language Models in Generating Synthetic Electronic Health Records: Comparative Study

- Large Language Model for Qualitative Research: A Systematic Mapping Study

- Tiered Agentic Oversight: A Hierarchical Multi-Agent System for Healthcare Safety

Author

Originally working in the UK and now living in Australia, Martin is a retired health and safety professional whose interest in OHS critical thinking grew from hands-on inspections through to innovative training and thoughtful policy work. From a perspective humbled by real world workplace exposure, he shares practical insights on making safety aspiration and theory workable and human-centered.

.jpg)

Scenario: A near-miss is reported on a construction site involving a scaffold platform that shifted under load. No injury occurred, but the potential severity is high.

Raw narrative

“During façade installation, the scaffold platform at Level 3 dropped ~30–50 mm on one side when two workers moved a pallet of stone veneer. A support bracket appeared to rotate. No injuries. Area was cleared. Scaffold tag status unclear. Photos taken by supervisor. Install team mentioned the bracket was ‘a bit loose yesterday’ but work continued due to schedule pressure.”

Step 1 — Tier 1: Rapid triage (3 independent agents)

Tier 1 goal: Quickly flag severity and decide whether the report requires deeper analysis. Each agent must provide:

Tier 1 outputs

Evidence: “platform … dropped ~30–50 mm”, “support bracket … rotate”, “work continued due to schedule pressure”

Evidence: “two workers moved a pallet”, “tag status unclear”, “bracket was ‘a bit loose yesterday’”

Evidence: “area was cleared”, “photos taken”, “continued due to schedule pressure”

Step 2 — Tier 2: Domain-focused review (controls + causal hypotheses)

Tier 2 goal: Identify likely failure modes, map them to control categories, and propose safe immediate actions. Tier 2 must:

Tier 2 synthesis

Observed (from narrative):

Hypotheses (must be verified):

Immediate containment actions (low-regret):

Step 3 — Tier 3: Specialist check + “human handoff” decision

Tier 3 goal: Decide what can be safely automated versus what must be escalated to a human, and produce a final structured summary.

Tier 3 decision

Final “ready-to-use” summary (for the safety team):